![Alphen aan den Rijn:

Ecolonia - the Dutch test case for sustainable town planning

Country:

a) Western Europe

b) Netherlands

Language:

Type:

Project, Concept, 1

Area:

District/Quarter, 20,000-100,000

Actors:

Local government, National government, Economic sector

Funding:

Local government, National government, Economic Sector

Topics:

Architecture and construction

Energy

Health

Housing (and new settlements)

Renewable resources

Water

Objectives:

Increase public awareness

Increase use of ecological building materials

Increase use of renewable resources

Reduce energy consumption

Reduce water consumption

Waste avoidance

Instruments:

Demonstration and pilot project

Integrated planning approach

Abstract:

The sustainable town planning project at Alphen aan den Rijn was commissioned by the Dutch national Environmental Agency in order to gain experience in the field of ecological town planning as well as in the area of ecological architecture. The project at Ecolonia is a remarkable achievement as it approaches the following areas of sustainability:

• emphasis on heterogeneity in urban planning and architecture in order to test different ecological approaches;

• rainwater utilisation;

• use of passive and active solar energy;

• implementation of energy saving concepts;

• reduction of water consumption;

• use of durable materials;

• design of flexible layouts;

• designing special soundproofing;

• special attention to the aspects of healthy living.

•

Concept and aims

In the mid-1980s the idea of the promotion of environmental awareness and energy saving building projects was given new impetus as the inter-disciplinary planning approach was being increasingly adopted in the field of ecological urban development. The intention of the Dutch demonstration project was to show the high quality of the knowledge already available. In consequence, the Netherlands Agency for Energy and the Environment (NOVEM) and the Ministry for Economic Affairs joined forces and commissioned a preliminary study on the feasibility of such a project in 1989. This initial step also included an inquiry with participants of the Ministry of Housing, Physical Planning and the Environment (VROM). The aim was to achieve a far-reaching consensus on the guidelines of environmental building and environmental conservation principles in order to identify the greatest possible basis for a sustainable estate.

After taking inventory of all the relevant guidelines, laws, national plans and political responsibilities, the involved ministries asked 17 architects to sketch out their ideas for an environmentally sound project in 1990. The aim was to construct a housing estate with approximately 100 dwellings. The architects had to concentrate on selected themes from the National Environmental Policy Plan. In 1989 the Dutch government published this plan in order to stimulate policies which would go beyond the statutory requirements of the policy field concerned. In the case of ecological urban planning, the national policy lines pay special attention to the areas of energy extensification, flow management, and quality improvement. The Dutch demonstration model implements these key principles by taking the following measures into account:

Energy extensification:

• the loss of heat should be reduced by the insulation of the individual houses, the installation of shutters (outdoors), and favourable positioning in relation to insulation;

• solar energy should be used through the incorporation of special garden rooms and sun lounges, as well as the particular zoning of room space;

• energy consumption should be reduced by a conscious building process and the energy consumption per residential unit was limited to a maximum of 300 MJ / m3 (low energy building materials, avoidance of energy-consuming construction methods).

Flow Management (Integral chain management):

• extra thought has to be given to the reduction of water consumption and the re-use of building materials (installation of flush toilets with minimal water usage, low-flow showers, apparatus with water-saving fixtures, selection of re-usable and renewable building materials, maximisation of the number of components that can be easily dismantled for re-use, installation of wooden floors between storeys as well as mineral wool in ceilings as a measure for noise insulation);

• special attention should be given to the use of ecological materials and the commitment to so- called organic architecture (careful selection of materials and components [e.g. cedarwood or European or Canadian hardwood instead of tropical woods], maximum use of granules from used concrete and brick, careful choice in the form and structure of spaces and building elements);

• the planning and implementation process should be open to flexible changes in construction and functions (creation of adaptable and easily extendible buildings, catering for combinations of living and working in the houses).

Quality improvement:

• one focus of quality improvement should be noise insulation inside and outside the house (especially soundproofing in facades and between rooms and installations, integration of a hanging system with rail of boards as fixed elements in order to avoid hindrance from drilling of holes in walls, provision of removable inner walls);

• health and safety should also receive special consideration (provision of open crawls in order to avoid radon gas, placing of smoke detectors in living and sleeping areas, use of fireproofed materials, extra fireproofed doors, fire escape routes with an attic window, placing of a straight staircase, entrance doors with safety glass, washing and drying facilities on the same floor, use of floor heating, avoidance of skirting-boards and wooden thresholds, installation of hanging kitchens and toilets, no dust collection corners);

• use of bio-ecological building principles and materials (avoidance of negative electromagnetic fields, use of non-toxic and water-soluble paints etc.).

In addition to theses guidelines the architects had to consider that the demonstration projects had to comply with the requirement of creating serialised buildings which are not limited to specific target groups but which will attract a wide range of buyers and will be affordable to most people. The architects involved had to design eight to eighteen buildings which integrated the above mentioned principles of sustainability. Finally, nine firms were selected to commission the final planning of the project.

Implementation

The 101 houses were constructed by nine architectural firms and, therefore, each group has its own ecological profile. However, in accordance with the construction guidelines the builders had to integrate certain themes of sustainability. The following ecological concepts have been put into practice:

1. Energy efficiency;

2. Minimisation of heat loss;

3. Solar energy use;

4. Organic architecture and durable materials;

5. Flexible construction;

6. Soundproofing;

7. Healthy building;

8. Bio-ecologically sound buildings;

9. Water consumption minimisation;

10. Traffic control;

11. Landscape concepts;

12. Social community concepts.

61 dwellings of the total of 101 buildings have heat-recovery controlled ventilation systems, 32 have mechanical ventilation without heat recovery, and the remaining eight dwellings are naturally ventilated. At nearly 80 dwellings solar collectors have been installed to the south. The east-west oriented buildings had not been equipped with solar collectors as the energy savings proved to be too low. Photovoltaics were rejected on financial grounds.

The minimisation of heat loss was the theme of a group of eighteen dwellings. Measures include wall construction of 120 mm thick limestone and a 130 mm thick solid thermal skin covered with 15 mm of plaster, the installation of blinds to provide shade in the summer, the equipping with particularly small windows to the north side and large ones to the south.

Ten dwellings in five twin houses were especially designed to experiment with the use of solar energy. These buildings use passive solar energy, as living areas are oriented towards the south and are fronted by a single-glazed conservatory for passive solar energy gains. All buildings are fitted with solar collectors for water-heating. Another group of eleven buildings incorporate passive and active solar energy use as they have additional solar collectors on the roof.

Organic architecture was the theme of another twelve houses. Ecological criteria like durability, maintenance level and embodied energy were all fundamental principles of their design. Cavity masonry of lime stone and burnt bricks were selected for massing. The roofs were covered with ceramic pantiles. European wood was used for the windows and untreated cedarwood was selected for other wooden parts.

Ten buildings demonstrate the advantages of flexible dwellings. Such houses have flexible external wall modules, changeable floor plans, moveable interior walls and variable installations. The inhabitants can alter both a room’s space as well as its function. An ensemble of staircase, supply shaft, and WC forms the core of the floor plan. The remaining rooms, including the kitchen, can be expanded or removed.

The ten buildings, which are designed by the Eindhoven Technical University, are test cases for soundproofing. The measures include low-noise heating and ventilation systems, the concentration of high noise-level rooms (kitchen, bathroom, stairwell, entrance) at the back of the building, noise protection in the remaining rooms by 150 mm limestone walls, and special construction of the bedroom (the quiet room) with an extra insulated timber frame and sound-deadening doors.

The twelve ”healthy buildings” pay tribute to the fact that health risks, such as allergies or psychological well-being, are increasingly becoming important factors of building design. The special design of these houses is characterised by sub-floor space heating, a vacuum system for the prevention of dust circulation, small landings on staircases etc. In addition, particular attention was given to the prevention of ”cold bridges”.

The area of bio-ecologically sound building saw the equipping of eight buildings with a solar collector for radiant heating walls which are developed in co-operation with industry. The problem of electromagnetic smog was dealt by with covering the floors with a 20 mm thick cork flooring and the painting of walls with natural paints. Furthermore, all these buildings have natural ventilation.

In order to disseminate the acquired know-how on sustainable methods of town planning, an information centre was established.

Actors and Structures

The client of the Ecolonia project was the Bouwfonds Woningbouw housing association. The urban planning procedure was executed by the Belgian architect Lucien Kroll from Brussels. The nine invited architects or architecture teams were BEAR-Architects from Gouda, Albert & Van Huut from Amsterdam, Hopman bv from Delft, J.P. Moehrlein from Groningen, Bakker, Boots, Van Haaren, and Van der Donk from Schagen, Lindeman c.s. from Cuijk, Peter van Gerwen from Amersfoot, Archi Service from Hertogenbosch and Vakgroep FAGO from the Eindhoven Technical University.

Finance

The Ecolonia project was co-financed by the Ministry of Economic Affairs and the Ministry of Housing, Physical Planning and Environment. The subsidies amounted 6 million Dutch guilders. An additional investment of 23,000 Dutch guilders per building had to be made. The cost per building varied between 180,000 and 300,000 Dutch guilders.

Evaluation and Statements

The Ecolonia project was run by the Bouwfond Woningbouw housing association, a private association which also has municipal representatives as members. Therefore, a close working relationship between the housing association, the municipal council, the architects, and other actors looked promising. However, the co-ordination process proved to be very time-consuming as departmental responsibilities had not been bundled up. Administrative insistence on sole responsibilities and inexperience in executing a sophisticated model project had to be overcome at a number of workshops and informative sessions. Nevertheless, this procedure led to difficulties in the planning and implementing process. In consequence, the funding approval process came under pressure and, therefore, a lowering of the ecological standards had to be accepted.

Source of Information

Ministry of Housing, Physical Planning and the Environment, (ed.) 1994: The Greenhouse Effect. Preventive Urban Actions in the Netherlands, Study by the International Institute for the Urban Environment, Delft, Den Haag

EA.UE, (ed.) 1994: New Sustainable Settlements in Europe. An Analysis of Experience of Seven Case Study Settlements, revised edition, Berlin

Personal contact with Roger Rovers, April 2000

Contact:

NOVEM

The Netherlands Agency for

Energy and the Environment

Swentivoldstraat 21

Box 17 6130

NL - 6130 AA Sittard

www.nove.nl

Citiy:

Alphen aan den Rijn :

Ecolonia is a part of the town Alphen aan den Rijn, which is located in the Dutch ”green heart” between Amsterdam, The Hague, Rotterdam and Utrecht. This central location was an outstanding argument for accepting Alphen aan den Rijn as the small town which is best suited for a demonstration project in the field of ecological urban development. The site belonged to the city council and was originally marshland that lay below sea-level. Ten years before the projected started, the land had been artificially drained by pouring on a three-metre deep layer of sand. The only natural characteristic of the reclaimed land is the watercourse.

Population: 68000

Project was added at 21.06.1996

Project was changed at 05.03.2001

Extract from the database 'SURBAN - Good practice in urban development', sponsored by: European Commission, DG XI and Land of Berlin

European Academy of the Urban Environment · Bismarckallee 46-48 · D-14193 Berlin · fax: ++49-30-8959 9919](---Ecolonia.I.txt.Engels_files/shapeimage_5.png)

![3.1 Ecolonia, Netherlands

Initiated in 1991, “Ecolonia was part of an expansion plan in the town of Alphen aan der Rijn, located between the cities of Amsterdam, The Hague, Rotterdam and Utrecht, in what is known as Netherland's 'green heart'”. The project was supported by the Netherlands Ministry of Housing, Economic Affairs, Environment and Spatial Planning (Blundell, 1992; Hans, 1995). “It consists of 101 semi-detached and terrace homes within a development of 280 units within an urban extension of Kerk en Zanen numbering 6000 dwellings, south of Alphen”.1 The Ecolonia project aimed to demonstrate and promote sustainable energy technologies, sustainable building practices, and more sustainable living practices (Blundell, 1992; Hans, 1995).

In 1989, the Netherlands government introduced the National Environmental Policy Plan that was very instrumental in the development of Ecolonia. The Plan, aimed at building industry, targeting mainly housing development, identified three major themes where significant steps needed to be made towards a sustainable and qualitative improvement for the citizens of the Netherlands by the year 2000. The three policy themes of that Plan were Energy Conservation, Life-Cycle Management and Quality Improvement. These themes and their further detailing provided programmatic considerations for the architects involved in the development of Ecolonia, and are referred to later on. Now let us look at the Ecolonia community design informed by the three themes.

The concept plan for Ecolonia was developed by Lucien Kroll, well known for his advocacy of an urban development form that fosters a relationship between people and their environment. His ideas are based on principles of natural expansion where a [development accommodates the needs of its community through building resilient ecosystems]. The following are the three themes within which housing schemes were considered in the development of Ecolonia.

Energy Conservation

Integral Life Cycle Management

Quality Improvement

All the ecological design concepts incorporated under the three themes aimed at reducing energy consumption (by at least 25%), reducing water consumption, reducing land use, reducing the rate of raw material extraction, and reducing fossil-fuel use. Also the development of Ecolonia aimed to expand public space and increase amenity. Integral Life Cycle Management and Quality Improvement are discussed with special reference to organic design, water and sanitation, organic agriculture and land use, transportation and economic viability, whilst energy conservation, discussed next, ultimately becomes integral part of the other two themes. All three themes are parts of a whole – sustainability as envisaged by Ecolonia developers.

3.1.1 Energy conservation

Design Features:

High thermal insulation

Ecolonia community development walls, roofs and floors were insulated using material with Rc = 4 m2 K/W for walls and roofs, and Rc > 3 m2 K/W for floors. Here “high insulation or R value refers to the insulative properties of materials, the higher the R value, the better the insulation. The practice of using higher R value insulation, in conjunction with tight building practices yields good results providing an environment that is efficient and comfortable. High insulation may mean increased short-term cost, but this will be offset over time by reduced fuel costs and a more comfortable living environments”.

Windows with a high thermal resistance

Double-glazing with external shading (roller-blinds) was used in Ecolonia. Windows (single or double glazing) are available in differing states of emissivity. Emissivity “relates to the amount of heat loss allowed by a window. The greater the number of panes in a window, the less emissivity it has. The creation of dead air spaces or air buffers between the panes further

decreases the emissivity of the window”. Ecolonia designers also used Low-E glass that reflects up to 90% of long-wave radiation (heat), but allows short-wave radiation (light) in. “Low-E glass will tend to keep heat energy inside the building during the winter, and keep heat energy outside the building during the summer”.

Compact building style

Smaller single family dwelling unit sizes designed for Ecolonia development was a major driver of social transformation and were replicated in other developments in the Netherlands “as the social and demographic profile of family and other household arrangements changes. Smaller unit sizes are designed to make more efficient use of interior spaces while retaining solar and ground access”. Higher density buildings create a “more compact, efficient and affordable residential development. Net densities for smaller unit sizes in Ecolonia range from 7 to 14 units per acre” (about 4050 square meters). The benefits of compact building style include: “lower impact on the natural environment, more compact and accessible neighbourhoods which promote community, potential for public transit integration, reduced infrastructure expenditures, reduced costs for materials and construction, and reduced servicing, maintenance and energy expenditures (life-cycle costs)”.

Solar energy for passive and active heating and hot water

The buildings should be designed in a way that maximises solar access and minimises wind exposure. The buildings in Ecolonia achieved correct orientation that was well aligned with the streets. In so doing Ecolonia increased human comfort through maximising passive solar energy and the demand for external energy was reduced. Buildings in Ecolonia were designed to collect solar energy with windows acting as the main collection source. This was done using passive designs: proper orientation building with 50 - 60% of the building glazing oriented to the sun (south exposure in northern hemisphere and north exposure in southern hemisphere) and active designs: solar collectors to warm an interior space of the building, but solar collectors collect solar heat mechanically by using additional external electrical energy to operate pumps, motors etc. Solar Water Heaters were used for water heating as well.

3.1.2 Organic design that considers the natural cycle (durability and maintenance)

Design Features:

Raw materials from the natural carbon cycle, such as wood cellulose, natural paints, resins were used in the development of Ecolonia, and cement was used only for later recycling

Recycled material, such as rubble and concrete granulate were used in the ground floor and plaster board derived from flue gas desulphurisation

Windows and frames made of local softwood, with hardwood lintels and sills and other easily replaceable materials and reusable components were used in Ecolonia.

“Recycling is seen as the third stage of energy and material conservation in the Reduce-Reuse-Recycle `trilogy'”. Materials to be recycled are timber and lumber, cabinetry, doors, and other wood items. Also precast and pre-stressed concrete slabs, steel structures and cladding, glazing, and other modular construction elements.

3.1.3 Water and sanitation

Design features

Reducing water consumption

In Ecolonia rainwater is harvested and used for irrigation, toilet flushing and car washing. Retention pond has been constructed at the centre of the Ecolonia community site. Mole drains are used to conduct water to the pond where “it is cleansed by a variety of wetland species, such as reeds and cattails. These vegetative filters help in breaking down the pollutants in water collected from road surfaces and chemical residues, in some cases leached from lawns and gardens”.

Constructed wetlands

This is sewage treatment that is different from the conventional sewage system where the sludge sinks to the bottom of the pit for anaerobic decomposition to take place. In Ecolonia, “shallow ponds are populated with water hyacinths and bull rushes that aid the natural processes of the sun rays, oxygen supplied by wind moving the water, and bacteria and algae are present in the pond. The plant material can remove large quantities of nitrogen and phosphorus, as well as sucking up toxins such as heavy metals and phenols into their plant biomass”. Furthermore, this plant material can be harvested and incinerated to dispose of the toxins and provide heat. “The effluent is free enough of any pathogens that it can be sprayed on the land to irrigate crops, thus returning water to the ground that has been cleansed in a distinctly more natural way”

Precipitation

Precipitation can be a great source of water for garden and greenhouse irrigation. When channelled inside a building, it can be used for many purposes: flushing toilets, washing clothes, watering indoor plants. “During temperate seasons, rainwater barrels can supply necessary moisture for a garden or herb plot, free of civic water consumption or sewerage charges. Eaves troughs can be emptied into purposefully designed barrels that have bottom mounted hose fittings allowing the gravity forced water to supplement natural precipitation when necessary”.

Water-saving showers, taps and toilets

Most of water-saving devices used in Ecolonia include faucet aerators with a discharge rate as low as 2 litres/minute, low flow shower heads with flow rates between 6 and 10 litres/minute, high efficiency toilets with flow rates between 2 to 6 litres/flush.

Other water-saving concepts and devices are front loading clothes washing machines using up to one third less the amount of water as conventional top loading models. Considerable water savings can be generated by not using the dish unless it is absolutely necessary and only when it is full. “Other water savings can be achieved by leaving a jug of water for drinking in the refrigerator so that it will remain cold, and the use of soaker or neoprene osmosis hoses on the lawn or in the garden”.

3.1.4 Organic agriculture and land use

Design features

food cycle

Organic techniques, such as composting, mulching, and using liquid and solid waste as fertilizer are used in Ecolonia. “It is an alternative to releasing toxic contaminants from herbicides and chemical fertilizers into the soil, surface and ground water. Organic techniques are important in long term use of the land for food production and the sustainability of soil because it recycles energy, nutrients and minerals with minimal damage to the local water supply and wildlife”.

3.1.5 Transportation

Design features

Traffic reconfiguration

Ecolonia is bounded on the west by a slow-traffic route from the city centre to the educational park, Archeon. An objective in designing Ecolonia was to reduce the amount of car-based transportation. Winkel centrum, is the local centre to the north of Ecolonia that provides a range of shops within a ten-minute walk to the regional rail station. The town-centre of Alphen aan den Rijn is about fifteen-minute walk from the station.

Within Ecolonia, walking and cycling are the main modes of transport resulting in low levels of noise, and improved safety. Car-based routes that are found in Ecolonia are designed for slow speed. The weakness of the traffic system in Ecolonia is that it does not make clear the separation between the different types of traffic. There are no marked parking bays or separate areas for cyclists and pedestrians. Areas designed for play and common areas are also often parked on.

3.1.6 Economic viability

Local employment opportunities created by the development of Ecolonia included two hairdressers and one doctor. Since Ecolonia was designed in such a way that there is good access to employment centres in the region, many of its residents already had stable jobs before moving to it. Moving to Ecolonia, among other reasons was precisely to be closer to the places of work.

There were housing “subsidies of 6,000,000 Dutch guilders that were contributed by the Ministries of Economic Affairs, Building Construction, Regional Planning and Environmental Protection”, all aimed at achieving the objectives of the Environment Policy Plan (NMP).

Modern energy and resource efficient community designs such as Ecolonia may appear to be more expensive at the outset, when compared to the cost of traditional community designs, “but the short term costs are offset by the long term benefits resulting from thoughtful planning and innovative design. The operating costs of these homes are significantly lower than those built in the surrounding community following normal practices” – business as usual (BAU) scenario.

3.1.7 Closing remarks

The community development project of Ecolonia was not aimed at 'green' residents but to demonstrate that environmental considerations in housing design can be attractive to all. According to Blundell (1992) & Hans (1995) environmental aspects of Ecolonia were found to be attractive and relevant to the home buyers and many of them stated that their environmental awareness has increased since moving to Ecolonia.

Ecolonia showed that more sustainable housing is possible in the Netherlands residential building sector. The initial step has been taken and those involved have learned a great deal and indicate they have developed their capacity to go further in future projects.

According to Van Der Ryn & Cowan (1996), positive design offers three strategies for addressing unsustainability: conservation, regeneration, and stewardship as mentioned in Part A. Conservation simply slows down the rate at which resources and energy are consumed, and unfortunately assumes that the damage must be done and the only recourse is to minimise this damage for the development (Van Der Ryn & Cowan, 1996). According to me, Ecolonia community development project achieved more of conservation and stewardship than regeneration for addressing unsustainability, though there were areas where positive design based on positive thinking was achieved, such as constructed wetlands, use of natural paints, passive solar harvesting, composting, and rainwater harvesting. But most design measures in Ecolonia, such as recycling, denser communities to preserve agricultural land, adding insulation, installing water-saving devices, and transportation were employed to reduce damage, than contributing to a net social and environmental gain. According to both Van Der Ryn & Cowan (1996) and Birkeland (2002) conservation alone cannot lead to sustainability since it implies a net loss in resource and energy use.

5. Bibliography

(www.arch.umanitoba.ca/sustainable/.../ecolonia/ecoindx.htm)

Blundell, J.P. undated. Ecolonia, Community planning, Alphen-aan-den-Rijn, the Netherlands. Architecture Review, London, March. 1992. London. Nr. 1141.[Online].http://www.arch.umanitoba.ca/sustainable/cases/ecolonia/eco024.htm. Accessed 5 August 2009

Hans, O. 1995. Technology and Performance Aspects of the Ecolonia Demonstration Project. Delft: TNO-Bouw.

in RCan. Innovative Housing Proceedings. Volume 3: Applications and Demonstrations. Ottawa. p 33-41. [Online]. Accessed 5 August 2009

Case Study: Motale Ben Mokheseng, student QwaQwa , South Africa, aug 2009 (fragment of the study)

source: Ben Mokheseng - Auroville, Ecolonia, Lynedoch - Sustainability ...

Student Number: 15553019

Course: MPhil Sustainable Development Planning and

Management (Renewable and Sustainable Energy)

Module Name: Ecological Design for Community Building

Lecture Name: Prof. Mark Swilling

Date: 11 August 2009

Title of Assignment: Ecological Design for Community Building

Declaration: I hereby confirm that the assignment is the product of my own work and research

and has been written by me and further that all sources used therein have been acknowledged.](---Ecolonia.I.txt.Engels_files/shapeimage_6.png)

An Innocent Abroad:

The Netherlands Green Buildings & People PART 5

by Ian Theaker

October 30, 1999 PART 5

Ecolonia, Alphen aan der Rijn

I'd heard of Ecolonia several years ago - a demonstration of green, low-rise residential development that had it all: energy

conservation, materials selection, solar heating, water conservation and natural stormwater management, green roofs.... I was greatly

looking forward to seeing how the buildings had weathered since their completion in 1992, and what had been learned. My hopes were

more than fulfilled.

conservation, materials selection, solar heating, water conservation and natural stormwater management, green roofs.... I was greatly

looking forward to seeing how the buildings had weathered since their completion in 1992, and what had been learned. My hopes were

more than fulfilled.

Ecolonia had its beginnings with an idea floated by W/E Consultants and BEAR Architects, to create a large and very solid

demonstration of the state-of-the-art of energy-conserving, environmentally-conscious design at the turn of this decade. The intent

was to educate and reassure the mainstream housing sector of the practicality of novel but well-established techniques - and

deliberately *not* to be a test-bed for experimental approaches. They managed to convince NOVEM (the agency for energy and the

environment) to fund a feasibility study.

demonstration of the state-of-the-art of energy-conserving, environmentally-conscious design at the turn of this decade. The intent

was to educate and reassure the mainstream housing sector of the practicality of novel but well-established techniques - and

deliberately *not* to be a test-bed for experimental approaches. They managed to convince NOVEM (the agency for energy and the

environment) to fund a feasibility study.

With the green light from the Bouwfonds Nederlandse Gementeen (the Building Fund of Dutch Municipalities) that both the economics

and the technical side of the project were promising, it evolved into a development of 100 single-family, terrace and semi-attached

dwellings at a green-fields site near the small rural community of Alphen aan der Rijn. Financed jointly by NOVEM and the Bouwfonds

Wonignbouw, the houses were intended for sale on the open market - so first costs had to be competitive, and building techniques

suitable for widespread mass production.

and the technical side of the project were promising, it evolved into a development of 100 single-family, terrace and semi-attached

dwellings at a green-fields site near the small rural community of Alphen aan der Rijn. Financed jointly by NOVEM and the Bouwfonds

Wonignbouw, the houses were intended for sale on the open market - so first costs had to be competitive, and building techniques

suitable for widespread mass production.

Three themes for the development echoed those of the NMP:

energy conservation and use of renewable energy;

life-cycle management, from extraction of raw resources to eventual

return of residual materials; and

quality and durability improvement.

life-cycle management, from extraction of raw resources to eventual

return of residual materials; and

quality and durability improvement.

These themes were further elaborated into nine areas of concern for the houses' architectural programs:

Energy Conservation:

reduced heat loss (BBHD - Bakker Boots Van Haaren Van der Donk)

solar energy (J.P Moehrlein)

energy conservation during construction (Architektenburo Hopman)

solar energy (J.P Moehrlein)

energy conservation during construction (Architektenburo Hopman)

Life-cycle Management:

water consumption and reuse of building materials (BEAR Architekten, Gouda)

extended lifespan & minimal maintenance (Architektenbureau Alberts & Van Huut)

construction for flexibility in use (Lindeman cs Architekten & ingenieurs)

extended lifespan & minimal maintenance (Architektenbureau Alberts & Van Huut)

construction for flexibility in use (Lindeman cs Architekten & ingenieurs)

Quality Improvement:

acoustic insulation (Workgroep Woningbouw en Energiebesparing)

health and safety (Peter Van Gerwen)

"bio-ecological" building (Architekten ArchiService)

health and safety (Peter Van Gerwen)

"bio-ecological" building (Architekten ArchiService)

A different architectural team was selected to focus on each of these themes, rather than get a cookie-cutter community from a single

design team. (Their names follow their focus, in brackets - I believe in credit where credit is due!) Overall planning of the community was

done by the renowned Belgian planner, Lucien Knoll.

design team. (Their names follow their focus, in brackets - I believe in credit where credit is due!) Overall planning of the community was

done by the renowned Belgian planner, Lucien Knoll.

At each intersection and at the ends of housing terraces, an extra storey on the buildings emphasizes the streetscape, and creates a

sense of entry and urbanity. The nine designs are mingled, to avoid uniformity, and located to create "squares" and social spaces, with

no setback from the streets. Streets, paths and squares are lit with high-efficacy lamps.

sense of entry and urbanity. The nine designs are mingled, to avoid uniformity, and located to create "squares" and social spaces, with

no setback from the streets. Streets, paths and squares are lit with high-efficacy lamps.

All of the buildings had the same general requirements:

environmentally-aware materials selections

crushed and recycled concrete aggregates

anhydrite cast floors

household waste separation and recycling facilities

solar water heaters

fossil-fuel space heating equipment to have high-efficiency, low-NOX burners

no use of tropical hardwoods

no use of bituminous products

no radon penetration to interiors

no use of CFCs in equipment and materials

crushed and recycled concrete aggregates

anhydrite cast floors

household waste separation and recycling facilities

solar water heaters

fossil-fuel space heating equipment to have high-efficiency, low-NOX burners

no use of tropical hardwoods

no use of bituminous products

no radon penetration to interiors

no use of CFCs in equipment and materials

Two energy targets were set for space and water heating and cooking; <300MJ/cu.m and <220 MJ/cu.m; the tighter standard was

required of the "Energy Conservation" theme buildings.

required of the "Energy Conservation" theme buildings.

The rural site, midway (about 30 kilometers) between Amsterdam, den Hague and Utrecht, had previously been designated for

increased growth. Like all of the Netherlands, the site is flat; an existing natural waterway bounds the south side. The Ecolonia houses

are only a part of a larger development, which totals some 300 dwellings in a variety of densities and forms. Knoll's plan created small

central lake to provide a focus for Ecolonia, to treat storm runoff and allow it to infiltrate into the ground; the little overflow from the

pond runs to the natural waterway via a small surface channel planted with rushes and cattails. Extensive native planting and gardens

are used to separate the buildings, with many deciduous trees for shade in summer, and allow solar exposure in winter.

increased growth. Like all of the Netherlands, the site is flat; an existing natural waterway bounds the south side. The Ecolonia houses

are only a part of a larger development, which totals some 300 dwellings in a variety of densities and forms. Knoll's plan created small

central lake to provide a focus for Ecolonia, to treat storm runoff and allow it to infiltrate into the ground; the little overflow from the

pond runs to the natural waterway via a small surface channel planted with rushes and cattails. Extensive native planting and gardens

are used to separate the buildings, with many deciduous trees for shade in summer, and allow solar exposure in winter.

Ecolonia was consciously designed with the pedestrian having priority. Streets have a variety of widths, but have narrow and winding

sections, and are mostly cobbled. There is no differentiation of car, pedestrian or bicycle paths, nor is there a through-route for cars.

Knoll used a mix of east-west and north-south blocks to create variety, deliberately sacrificing optimal solar exposure of the housing.

Even so, almost all of Ecolonia's houses have a significant passive solar contribution, and active solar collectors.

sections, and are mostly cobbled. There is no differentiation of car, pedestrian or bicycle paths, nor is there a through-route for cars.

Knoll used a mix of east-west and north-south blocks to create variety, deliberately sacrificing optimal solar exposure of the housing.

Even so, almost all of Ecolonia's houses have a significant passive solar contribution, and active solar collectors.

There were several building design responses especially worthy of note. Moerhlein and BEAR selected wood-frame construction - as

yet unusual in the Netherlands - largely on the basis of lower environmental impact over the life-cycle than the more common brick,

concrete or lime-sandstone block.

yet unusual in the Netherlands - largely on the basis of lower environmental impact over the life-cycle than the more common brick,

concrete or lime-sandstone block.

Several houses used recycled wall and roof cellulose insulation - with detailing that reflects the warning by building scientists from the

Netherlands Organization for Applied Scientific Research (TNO)to ensure that avoiding damp is imperative. One designer proposed

compressed cellulose insulation below the floor slab - which was rejected due to this concern.

Netherlands Organization for Applied Scientific Research (TNO)to ensure that avoiding damp is imperative. One designer proposed

compressed cellulose insulation below the floor slab - which was rejected due to this concern.

All the houses underwent airtightness testing during construction, to standards considerably higher than those required by code.

Water-conserving fixtures were universal; composting toilets were avoided due to concerns with proper operation and maintenance by

the owners. BEAR collected rainwater for toilet flushing and clotheswashing, and recovered heat from wastewater.

the owners. BEAR collected rainwater for toilet flushing and clotheswashing, and recovered heat from wastewater.

Moehrlein incorporated solar conservatories in their buildings, but they were found to overheat in the summer due to the lack of

shading (and - my surmise - insufficient thermal mass).

shading (and - my surmise - insufficient thermal mass).

Several designs (BBDH, Moerlein, Lindeman and Van Gerwen) had balanced ventilation via heat-recovery ventilators; the others used

switched or continuous exhaust fans with window-frame inlets; and one used exclusively natural ventilation through carefully-placed

window-frame inlet and outlet vents.

switched or continuous exhaust fans with window-frame inlets; and one used exclusively natural ventilation through carefully-placed

window-frame inlet and outlet vents.

Most buildings followed the Dutch standard practice of hydronic heating, but with radiators oversized according to practice at the time

to reduce temperature differentials and pumping energy. In most cases, the high-efficiency boilers supplement the solar domestic

water heaters as required; Hopman also had solar collectors for space heating. Two designs had hot air/furnace heating systems -

uncommon in Holland.

to reduce temperature differentials and pumping energy. In most cases, the high-efficiency boilers supplement the solar domestic

water heaters as required; Hopman also had solar collectors for space heating. Two designs had hot air/furnace heating systems -

uncommon in Holland.

ArchiService's design was unique in several respects. These were the only homes that had vegetated roofs. Rafters were covered with

20mm cork and a 1.3mm EPDM membrane; sloping roofs were further insulated with 50mm of mineral wool, and flat roofs with expanded

clay granules. These were then covered with 150mm of peat substrate and grass turfs. As well, in these buildings, particular attention

was paid to avoiding electromagnetic fields, and global and cosmic radiation. Most interesting to me was the design of hydronic radiant

"heat walls", developed in conjunction with suppliers. These consist of plaster applied over cast lime-sandstone blocks that have

channels for hot water tubing. Insulation is placed outboard of the blocks, and the exterior finish is brick.

20mm cork and a 1.3mm EPDM membrane; sloping roofs were further insulated with 50mm of mineral wool, and flat roofs with expanded

clay granules. These were then covered with 150mm of peat substrate and grass turfs. As well, in these buildings, particular attention

was paid to avoiding electromagnetic fields, and global and cosmic radiation. Most interesting to me was the design of hydronic radiant

"heat walls", developed in conjunction with suppliers. These consist of plaster applied over cast lime-sandstone blocks that have

channels for hot water tubing. Insulation is placed outboard of the blocks, and the exterior finish is brick.

Lessons Learned

In subsequent monitoring, seven of the nine Ecolonia designs met their heating energy targets of a 25% reduction from

current standard practice in 1991; their annual primary energy consumption varied from 181 GJ/cu.m (Archiservice's

"bio-ecological" design) to 288 GJ/cu.m (226 to 916 cu.m of natural gas for space heating; numbers are normalized for a

standard 300 cu.m volume). The other two projects exceeded their targets only slightly.

current standard practice in 1991; their annual primary energy consumption varied from 181 GJ/cu.m (Archiservice's

"bio-ecological" design) to 288 GJ/cu.m (226 to 916 cu.m of natural gas for space heating; numbers are normalized for a

standard 300 cu.m volume). The other two projects exceeded their targets only slightly.

Solar energy - even with the Netherlands' cloudy, rainy winters, and with sub-optimal building orientation - contributed to

this performance, especially in the shoulder seasons. (Take note, Vancouver designers!) However, many collectors required

fine-tuning and commissioning the first year.

this performance, especially in the shoulder seasons. (Take note, Vancouver designers!) However, many collectors required

fine-tuning and commissioning the first year.

Annual electrical energy varied from 2765 to 4374 kWh/household, comparable to 1991 average consumption of 3079 kWh.

(Compact fluorescent use was already standard practice.) PV arrays were not used due to high initial cost, except for small

ones in the BBHD designs, for pumping through the solar water heaters.

(Compact fluorescent use was already standard practice.) PV arrays were not used due to high initial cost, except for small

ones in the BBHD designs, for pumping through the solar water heaters.

Five of the nine designs failed to meet the high air-tightness standard, indicating that more detailing and on-site supervision

would be beneficial.

would be beneficial.

As mentioned before, solar conservatories and rooms with large south-facing glazing for passive solar heating, require

shading (and probably thermal mass) to prevent summer overheating.

shading (and probably thermal mass) to prevent summer overheating.

Heat recovery ventilators were found to be significant electricity consumers, and did not make large contributions to

heating energy savings in the Dutch climate. Further, they were the least satisfactory to the occupants, due to their

continuous noise. It was recommended that warm ventilation air should in future be supplied to the living rooms, rather than

the bedrooms - a contradiction to Canada's National Building Code.

heating energy savings in the Dutch climate. Further, they were the least satisfactory to the occupants, due to their

continuous noise. It was recommended that warm ventilation air should in future be supplied to the living rooms, rather than

the bedrooms - a contradiction to Canada's National Building Code.

Building material selections for lower environmental impact was a positive experience for the designers and builders.

Crushed concrete aggregate use was straightforward; alternatives to PVC plastics were easily found, with no compromise in

quality or service; anhydrite concrete floors were healthier for the workers, improved airtightness and provided smoother

surfaces. Wood-framing reduced life-cycle environmental impact compared to constructions more common in the

Netherlands, but required additional care in construction, and in maintenance (no surprise to Vancouver's Barrette

Commission...) Laminate use was successfully limited; but too few interior finish options offered to the buyers resulted in

later modifications - and materials waste.

Crushed concrete aggregate use was straightforward; alternatives to PVC plastics were easily found, with no compromise in

quality or service; anhydrite concrete floors were healthier for the workers, improved airtightness and provided smoother

surfaces. Wood-framing reduced life-cycle environmental impact compared to constructions more common in the

Netherlands, but required additional care in construction, and in maintenance (no surprise to Vancouver's Barrette

Commission...) Laminate use was successfully limited; but too few interior finish options offered to the buyers resulted in

later modifications - and materials waste.

Airtight floors barring radon penetration, and selection of finishes with low emissions, improved occupants' perception of air

quality inside the homes.

quality inside the homes.

Residents were most satisfied with the hydraulic heating systems - particularly the radiant floors and walls. They were less

satisfied with the hot-air systems, especially with their lack of individual control of temperature in each room, dry and dusty

air, noise, and distribution of cooking odorous. These last two complaints were also leveled at the heat-recovery ventilation

systems. The wholly natural ventilation system gave the most satisfaction; and then the exhaust-only systems.

satisfied with the hot-air systems, especially with their lack of individual control of temperature in each room, dry and dusty

air, noise, and distribution of cooking odorous. These last two complaints were also leveled at the heat-recovery ventilation

systems. The wholly natural ventilation system gave the most satisfaction; and then the exhaust-only systems.

Construction costs were kept competitive - but only after the original designs were re-examined for savings. Prices ranged

from 191,000 to 298,400 NLG in June 1992, comparable to market prices for the average homebuyer.

from 191,000 to 298,400 NLG in June 1992, comparable to market prices for the average homebuyer.

I spent a fine afternoon wandering the site, looking and photographing the buildings, streets and squares. The houses are all in fine

shape; and ArchiService's grass roofs, and the vine-covered trellises at the corners of the BEAR designs are especially beautiful. The

pond creates a very healthy, tranquil - and desirable - focus to the community; it is largely surrounded by reeds, with a resident family

of ducks, which delighted the small kids I saw playing as I sat on it's shore. The kids had no fear playing in the streets, and the design

was such that a parent could easily keep an eye on them from their homes. Anton Alberts' brick houses struck an odd note, with their

tilting rooflines and window frames - but fit superbly with their gorgeous gardens (one of the ducks was peacefully asleep on the patio

between the house and the reeded overflow channel). Obviously, their residents take a great deal of pride in their homes, and for

good reason.

shape; and ArchiService's grass roofs, and the vine-covered trellises at the corners of the BEAR designs are especially beautiful. The

pond creates a very healthy, tranquil - and desirable - focus to the community; it is largely surrounded by reeds, with a resident family

of ducks, which delighted the small kids I saw playing as I sat on it's shore. The kids had no fear playing in the streets, and the design

was such that a parent could easily keep an eye on them from their homes. Anton Alberts' brick houses struck an odd note, with their

tilting rooflines and window frames - but fit superbly with their gorgeous gardens (one of the ducks was peacefully asleep on the patio

between the house and the reeded overflow channel). Obviously, their residents take a great deal of pride in their homes, and for

good reason.

I also had a chance to speak with Martin Regenboug, one of Ecolonia's first residents, and steward of the Informatiecentrum Ecolonia.

He is the very satisfied owner of one of ArchiService's "bio-ecological" row homes.

He is the very satisfied owner of one of ArchiService's "bio-ecological" row homes.

He obviously loves his terrace house, and the community - he was most generous with his time, information and hospitality. Martin found

me sitting in the small grassed space behind his home, where I was watching (several!) flocks of birds feed and chatter in the

vegetation that covered his roof. We had tea in his back yard, at a beautiful handcrafted birch table that once formed the base of a

model of Ecolonia, for the benefit of tourists like me. He was especially happy with the wall heating system - silent, comfortable, and

economical. He could not recall *any* problems with any of the homes - and he's been keeping track since the beginning.

me sitting in the small grassed space behind his home, where I was watching (several!) flocks of birds feed and chatter in the

vegetation that covered his roof. We had tea in his back yard, at a beautiful handcrafted birch table that once formed the base of a

model of Ecolonia, for the benefit of tourists like me. He was especially happy with the wall heating system - silent, comfortable, and

economical. He could not recall *any* problems with any of the homes - and he's been keeping track since the beginning.

Apparently, general interest in Ecolonia has died down in the past few years; I was the first visitor he'd had in months. It seems that its

lessons have already been internalized by the Dutch mainstream - either that, or the novelty value has disappeared. He was

disappointed, however, in the lack of environmental fervour exhibited by his neighbours, whom he felt took the community, and what it

represented, for granted. He told me that the market value of Ecolonia homes is significantly higher than the other homes in the larger

surrounding development, for several reasons. The proximity to the pond, the lower operating costs, and the healthy construction are

all selling features that command a premium - much the same experience in Village Homes in Davis, California. Are any mainstream

Canadian developers in the crowd.

lessons have already been internalized by the Dutch mainstream - either that, or the novelty value has disappeared. He was

disappointed, however, in the lack of environmental fervour exhibited by his neighbours, whom he felt took the community, and what it

represented, for granted. He told me that the market value of Ecolonia homes is significantly higher than the other homes in the larger

surrounding development, for several reasons. The proximity to the pond, the lower operating costs, and the healthy construction are

all selling features that command a premium - much the same experience in Village Homes in Davis, California. Are any mainstream

Canadian developers in the crowd.

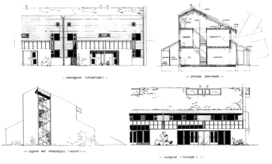

pre- study peter van gerwen

Quartiere ecosostenibile in Olanda

Nato all'inizio degli anni '90, in Olanda, nel comune di Alphen aan den Rijn, Ecolonia e' un quartiere sperimentale che rappresenta ancora oggi un ottimo esempio di architettura sostenibile.

La realizzazione degli edifici ha seguito il National Environmental Policy Plan del governo olandese (1989), che si basa su tre linee guida fondamentali: conservazione dell'energia, gestione dell'intero ciclo vitale e miglioramento qualitativo delle condizioni di vita.

101 alloggi, per 300 abitanti, su un'area di 2700 mq, la cui progettazione, affidata all'architetto Lucien Kroll, si basata sui principi base della sostenibilità ed è stata implementata da una serie di linee guida di altri nove architetti coinvolti nella realizzazione.

L'idea degli alloggi ha come fondamento la conservazione energetica: riduzione dei consumi e quindi delle fonti energetiche tradizionali, sfruttamento di fonti rinnovabili e sostenibili, gestione oculata dei consumi quotidiani e ottimizzazione dei sistemi di climatizzazione a basso consumo.

Integrated chain management, ovvero la gestione globale della catena di produzione: progettare con un occhio all'intero ciclo di vita di un oggetto, partendo dalla materia prima, la sua realizzazione, il suo smantellamento, fino al suo riutilizzo.

Tre le strategie per il risparmio energetico: la conservazione del calore mediante isolamento termico, uso dell'energia solare e consumi energetici globali; ma anche una gestione globale delle risorse, come l'acqua potabile, i materiali edilizi ecocompatibili e la considerazione della durata e dell'adattabilità delle costruzioni. Infine un miglioramento generale della qualità abitativa mediante il raggiungimento di prestazioni acustiche, soluzioni tecniche per aumentare la salubrità indoor e la sicurezza degli utenti.

Le strategie sono però state seguite ed applicate in maniera diversa ad esempio a seconda dell'orientamento e della posizione degli edifici e degli alloggi presenti nel quartiere; ad esempio in 18 unità orientate a nord-est o sud-ovest, essendo importante la conservazione del calore, le facciate sono state ricoperte con uno strato di 130 mm di materiale isolante, e di 15 mm di intonaco. Le 80 case esposte a sud hanno invece pannelli solari per il riscaldamento dell'acqua. In 61 edifici c'è un sistema integrato di riciclo dell'energia che sfrutta un condensatore che recupera il calore dall'aria in uscita dalle case e lo trasferisce all'aria fredda che entra. Sono 32 invece le abitazioni senza recupero del calore, mentre 8 sfruttano la ventilazione naturale.

Nonostante le differenze, ogni abitazione è pensata come una piccola unità compatta. Il contenimento delle dispersioni di calore è ottenuto in ogni abitazione mediante finestre con doppi vetri ad alto coefficiente di isolamento termico e l'isolamento di pareti e pavimento con cellulosa di legno riciclata. Infine le case sono schermate con alberi frondosi, che garantiscono un ombreggiamento d'estate, senza impedire l'ingresso del sole in inverno.

Anche l'acqua è un elemento fondamentale, così come lo è nella tradizione olandese; il punto centrale di Ecolonia è uno stagno naturale attorno al quale sono stati costruiti gli edifici. Le acque di scarico del quartiere che in parte finiscono nella rete fognaria, in parte in realtà vengono assorbite dalla vegetazione dello stagno. La pioggia è raccolta dai tetti verdi delle abitazioni, conservata e riutilizzata per innaffiare i giardini o per gli scarichi dei bagni.

All'interno del quartiere gli spostamenti avvengono perlopiù a piedi o in bicicletta, e le strade sono a scorrimento lento, con un'organizzazione della viabilità finalizzata alla coesistenza pacifica dei diversi mezzi.

Ecolonia, anche se pensata ormai qualche anno fa, rimane un ottimo esempio di quel che significa equilibrio; equilibrio fra ambiente, società ed economia. Tutto da imitare.